The Roman Emperor Augustus is said to have been the first recorded coin collector in history. Having idiosyncratic personal hobbies was a feature of the second great Caesar. It was said that he often gifted ancient coins from his collection to friends, family, and visiting dignitaries. During the middle ages coin collecting was referred to as the “hobby of Kings” - when learning returned to Europe, many a prince tried to emulate the mannerisms and pastimes of the Caesars.

Collecting is a peculiarity of the human condition - probably best explained by our earliest need to conserve food and produce for lean hunting months. Munger once quipped: “it’s not hard to be happy if you’re a collector and don’t run out of money”. He also noted that it didn’t really matter what one collected in this regard, the “smart-assed” example being mistresses.

Americans brought their own flavour to the typical pursuit of antiquarians. “Trading cards” made their first appearance in the late 1800s as a throw away item included with cigarette packets. They featured popular icons and spotrs stars. If you bought cigarettes you might discard the trading card quickly - and someone else might have picked it up. An early form of viral advertising.

At first these were not seen as collector’s items. Unlike ancient coins they weren’t fungible, beloved by wealthy hobbyists, nor did they have the essential element of extrinsic value: value that is acknowledged by a sufficiently large number of other enthusiasts. Critical mass in this respect was only reached in the 1950’s. Even then this was reserved for a select group of rare (that is the lack of supply) trading cards, epitomised by the legendary 1952 Mickey Mantle card.

Somewhere between 1950 and the early 1980’s some trading cards took on characteristics more commonly associated with a store of value. Of course this dynamic had long been associated with rare-coins, in part because rare coins (like certain Victoria-era gold Sovereigns) themselves were composed of sufficiently large quantities of rare and valuable metals. In both cases, however, the more that they began to resemble money, or indeed an investment, the more likely it was that nefarious actors would emerge trying to steal some of that value.

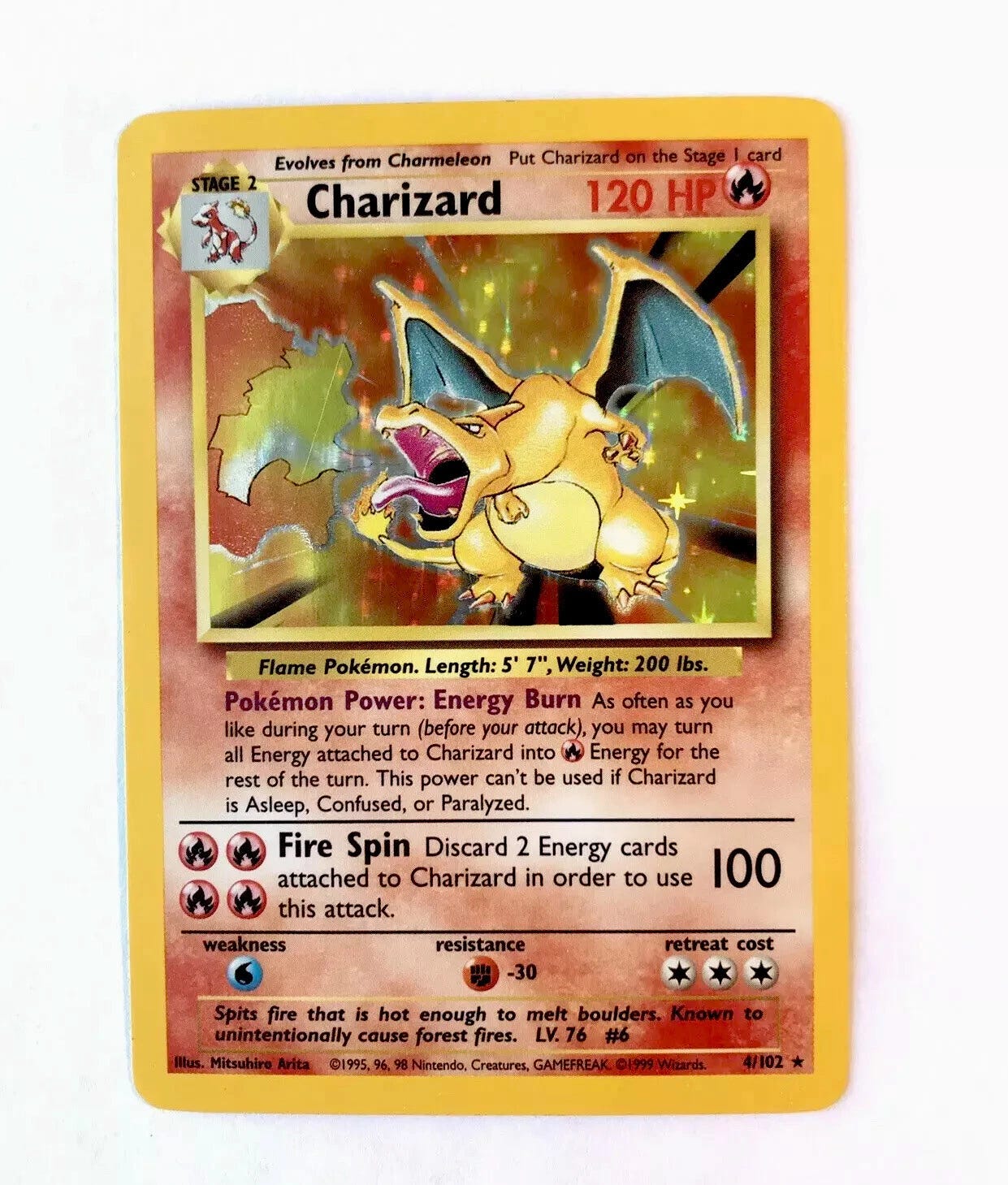

In the trading card context, the most notorious examples of counterfeit products had typically involved a few legendary issues: the aforementioned Mickey Mantle card, Michael Jordan’s player card, and ultra rare game trading cards like the 1999 1st Edition Charizard Pokemon card. Over time services like authentication and grading became unusually value additive - especially for serious collectors, and investors. As of this writing an unverified, ungraded 1st Edition Charizard may trade for as much as $5,000 USD. A verified, grade 10 card equivalent trades for nearly $250,000.

In 1985 a group of seven American coin dealers, including later President David G. Hall, founded Professional Coin Grading Service (PCGS). The market for collector coins in 1980 was described by Hall: ‘To put it bluntly, a lot of people were getting ripped off.’ By this time the market for grading and authenticating coins was highly fragmented, which inevitably meant corruption and inefficiency. ‘Overgraded’ (i.e. a dodgy coin dealer/grader produced documents that overrepresented the rarity and value of a coin or portfolio) and misrepresented coins were rife. It got so bad that the Federal Trade Commission was called in to investigate. The low trust nature of the industry threatened the livelihood of those dealers who decided not to leave their integrity at the door.

PCGS was formed after Hall, along with a number of other ‘high quality’ coin dealers and appraisers came up with the idea for an expanded ‘sight unseen’ market for rare coins. Hall himself had run an embryonic version of this for coins he himself had graded since 1983. At a ‘coiners’ convention, Hall pitched the idea to his trusted group of contemporaries - they all jumped at it, and demanded to be made authorised dealers of this new marketplace. Hall and his business partner put up $50,000 together, and the other five dealers put up $10,000 a piece. PCGS was formed. He would later say: ‘it was the best investment any of us made in our lives’.

This marketplace would need something to attract dealers, collectors, and investors - and that would be a widely recognised guarantee of authenticity. A standard if you will. “3rd party grading” - as it came to be known - took off. When PCGS opened their doors for business in February 1986 they received 18,000 coins to grade. The next month that number doubled.

Sounds a lot like ratings, doesn’t it?

Along the way PCGS came up with a number of innovations along this core grading concept. They standardised a way for coins to be encapsulated in plastic, with attached serial numbers that would denote ownership and a history of grading and appraisal. They rolled out a registry of all the coins they had graded. The so called ‘set registry’ is openly available, even today.

In 1991, Hall founded Professional Sports Authenticator (PSA), under a similar aegis. This has, however, been a market beset by consistent controversy. When PSA was first launched, it was initially resisted by card retailers and card dealers. They were naturally much more sceptical of a 3rd-party grader and authenticator and initially thought it would cut into their business. Sports cards, for example, are much more easily copied than coins. The typical term for a counterfeiting in the card context is ‘trimming’ - coming from the fact that these cards are trimmed off a piece of paper. The serrated edges of coins play an important role in their own regard. In commercial currency, coin edges are “milled” so as to stop people “shaving” the edges. The base metal used in most coinage is typically more valuable than their face value.

In time PSA would come to occupy a somewhat analogous position to PCGS in a variety of sports cards markets, as well as in sports memorabilia generally. Periodically, however, PSA would find itself in hot water. This included at least one run in with the FBI and numerous instances of large scale litigation. The two main issues PSA faced historically was the false grading of trimmed cards and misleading claims that they were properly insured for cards they had custody of while grading and authenticating them. In the former case, PSA would periodically offer to refund the full value of traded cards - notably in several issues where the traded card was worth well over $1M.

One of the key aspects of grading, authenticating, and indeed the liquidity provided by various marketplaces, was that it opened the market up to entirely new cohorts of buyers who wouldn’t have even got into collecting in the first place. It also expanded the total nominal value of the markets that were amenable to 3rd party grading. Authenticating collectables simply verifies that they are what they are claimed to be - grading, however, stratifies items on their condition. This is another essential element that gives some items immense value, and others none at all.

By the late 1990’s Hall had branched out into stamps and autographs. In 2000 the company listed shares on NASDAQ. By the mid-2000’s, the company was under the leadership of CEO Michael Hanes. His strategy took the company on a difficult turn. By this stage, and now trading under the broader Collectors Universe (CLCT) banner, the company had grown in part due to M&A. Several deals augmented the established core businesses. Some were as entrées to new markets. In 2005 they entered the jewellery authentication business. They did this by acquiring two businesses: GCAL (Gem Certification and Appraisal Lab) for diamonds, and AGL (American Gemological Laboratory) for coloured stones. To fund these acquisitions, management executed a secondary offering. In four short years the Jewellery business took CLCT from $8M in EBITDA to negative $3M. In 2009, Hanes left the company after GCAL and AGL were disposed of. In the depths of the GFC, the board decided to tender for 20% of the shares outstanding via a Dutch auction.

The GFC, ironically, was a great time for CLCT. While investors and the wider public grew sceptical, if not completely hostile, to public equity and real estate markets, so called ‘whales’ turned up in droves to park hard currency in hard ‘assets’. 2008-2010 saw one of the most prolific bull markets in rare coins in memory. During the 2010’s the business hit its stride. CLCT was (and indeed still is) the market leader in its core business; it authenticated 3.1 million coins in 2017. The company authenticated 1.5 million trading cards in 2017. CLCT authenticated 300k autographs in 2017, The insured value of all of these collectibles totalled $2.3 billion in 2017. 2018 presented a difficult year for the company when a turbulent Q4 caused the company to cut the dividend in half. Unencumbered by the cash burning activities of the past, CLCT operated with a healthy cash balance up until this period, funding ever greater dividends with cash on the balance sheet. At year end 2018, the collecting space faced one of its most turbulent periods. The subsequent pandemic period would see this dynamic swing violently back in the other direction.

By 2020 the business basically broke down in the following way: CLCT derived the vast majority of its revenues from authentication and grading consisting of fees ranging from $1 to over $10,250 per item. This was mostly based on the type of collectible authenticated or graded, the turnaround times and the specific service selected by the customer. CLCT would sometimes charge higher fees for faster turnaround times. Germane to this discussion was that CLCT generally did not charge a fee based on the value of the underlying collectable - in fact only some peripheral services charged on this basis. In 2017, CLCT’s authentication and grading fees, per item processed, for all of its businesses averaged $12.82 and averaged $14.92 per coin. These numbers can be contextualised against the entire insurable value of the all the items CLCT valued in any given year - verging on $2.4B in 2019, a year in which they made slightly more than $72M in revenues.

Since customers were not very price sensitive given the value proposition CLCT offers (i.e. a small fee to authenticate and grade a collectible, which greatly increases its value in the eyes of other buyers), CLCT was able to consistently generate 60% gross margins. EBITDA margins, pre-Covid, peaked at 23%. The balance sheet consistently had a net cash position. Importantly this was a service-only business, it required virtually no capital and very little CapEx.

Authentication and grading works by a customer initially posting an item to CLCT. The company employs expert graders who then grade the collectable via a system of double blind reviews. A senior grader then approves or denies the final verdict. Sometimes included in this service was the plastic encapsulation, as mentioned before, but CLCT would also maintain a proprietary ledger of all their graded and authenticated items. What drove the business was in their ability to recruit expert graders, and a typical standards moat that accrued to the largest, most widely recognised 3rd party service. Both of these aspects feed back on themselves - expert graders give legitimacy to the brand, and the brand and scale that accrued allowed CLCT to pay graders the most. Recognition, feedback, and ultimately latent pricing power.

The Pandemic affected collectables demand in a way that no other event could have. The lockdowns, the time spent inside, and the wide public interest in NFT’s and other fringe collecting hobbies belied an underlying latent demand for grading services. In 2019 the company typically received 68,000 items per week to grade. That number was 250,000 by mid 2020. Unfortunately the company was woefully underprepared for the demand. By this time the company was being run by CEO Joe Orlando, under the auspices of what would later be revealed the be a pretty checked-out board of directors chaired by former Steinway & Sons executive Bruce Stevens. Nearly 35 years into its run as a public company, CLCT had lost most of its roots with its long-time founding employees. A number of executives who ran the business over the years proved to be completely ignorant of what made the business tick.

Customer complaints began to surface on internet message boards even before the Pandemic began. It was rare for the company to answer the phone, and rarer still if you could actually get a hold of human being who could address the status of a grading. Part of this was later attributable to cost-cutting and furloughs affected by the lockdowns, but it became clear to a few that the business was not really interested in aggressively monetising itself. This became apparent when Conor Haley’s Alta Fox purchased shares during the March 2020 equity market rout. Haley encouraged the board to do likewise (that is repurchase shares) but was firmly rebuffed. While Alta Fox would come to own 5% of the company (more than every single board member combined), they were also blocked from communicating with the company after they presented a series of reforms and business rationalisations in April.

While it was pretty clear that CLCT was not all that operationally efficient before the Pandemic (the company always had a sizeable back log) it was also true that they were not meeting their obligations to shareholders and customers in other ways. This was communicated by Haley in two key areas where the company was falling behind: 1). In the monetisation of its backend proprietary data, and how CLCT was falling behind in areas like digital collectables, and 2). In the monetisation of its other services the company was ostensibly providing free of charge already, namely in storage and physical custody fees. In Alta Fox’s conception, the company could begin to look much more like NASDAQ and Bloomberg, and less like a typical professional services firm. This made sense as CLCT controlled two dominant, monopoly positions in grading and authentication and had barely developed the commercialisation of that position since the 1990s.

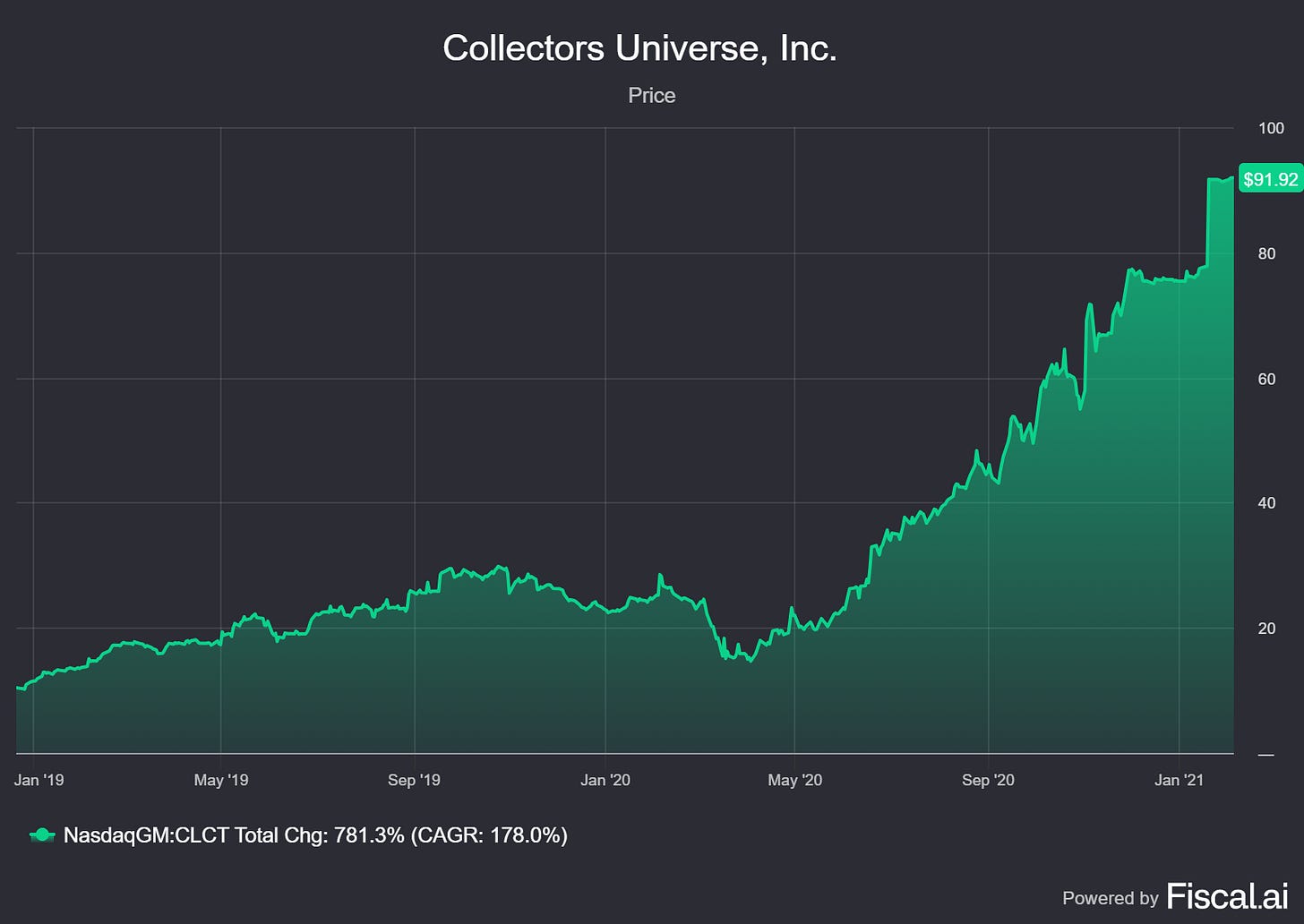

Importantly, the company had a significant amount of economic goodwill on its balance sheet that it could otherwise capture, without the need for any additional reinvestment - at a time when interest in collectables was booming. In a very strange series of events the company illustrated this very point when they announced that they would offer a much more expensive expedited grading service. This had the strange effect of both increasing demand and supply simultaneously. You don’t see that very often. With even the meagre efforts of the board, although significantly more effort given by management, the rather tepid results of the past inflected in an unprecedented way:

Alta Fox eventually went on an out-and-out activist campaign in June of 2020. The board responded by appointing an additional 3 members to their group, none of which represented the activists interests, and eventually signing off on a limited share repurchase plan. CLCT had much more regularly paid dividends than repurchased stock. In any event the triple concurrence of greater volumes, greater pricing, and better capital allocation affected a very predictable outcome:

In late 2020 an investor group led by serial entrepreneur and collecting enthusiast (with nearly 13,000 PSA registry entries) Nat Turner, with backing from Stephen Cohen, and D1 Capital Partners, along with a veritable panoply of sporting icons (including Kevin Durant) made a bid for the company at $75.25 per share valuing CLCT at $700M. In early 2021 a final bid was put in by the group for $92.00 a share. The board approved the deal unanimously, and Turner took up the position of Executive Chairman, and the rest as they say is history.

An organic pricing and volume story - as well as the layering on of additional incremental service revenue - stolen away from the public. Here’s to the next one.

Forbes.

“Stolen market value” is a good description - also applies to Swedish Match, which like CLCT, was acquired in the middle of a boom in demand for its products. SWMA didn’t feature a co-opted board member like CLCT did (as Davey’s Blog noted), but did illustrate how short-term perspectives and incentives for shareholders could push a deal past a 90% acceptance threshold. I owned both targets, voted no twice, and feel pocketbook regret.

This was fantastic, thank you.

If open to requests, would love if you could hyperlink to some of the more notable sources throughout the post. For example, would love to know the source for the Munger quote, the Charizard pricing, the >3x increase in 2020 demand, etc. Just my two cents - thanks again!