Not held.

I briefly covered Grindr earlier this year. Naturally, without a single share lining my portfolio, it has rallied 45% since. As a former, and potentially future, President of the United States once remarked: ‘many such cases’.

The crux of my initial interest in the company was the following:

A couple of characteristics jumped out at me straight away. Firstly, the product is widely derided - some might even say hated - by its users, despite the fact that it is still ubiquitous. This kind of cognitive dissonance has been a hallmark of other great, durable products - mostly in technology. Secondly, the product has seen little material changed since its initial commercial breakthrough in the 2000’s. The lack of meaningful innovation is partly explained by its corporate history (more on this later), but also by the fact that it doesn’t really need to do much to maintain its hold on users. Finally, mismanagement has resulted in the platform being poorly commercialised. In other words there are opportunities for significant value creation (sometime) in the future. It’s my opinion that the company resembles more of an online classifieds business rather than a traditional online dating app.

Grindr’s recent Investor Day, along with prodding from a friend on Twitter, has occasioned me to take a deeper look.

My initial resistance to viewing Grindr as investable was a quadruple reluctance based on:

Management (question marks abound),

Capital structure (the company has a significant debt load),

Capital returns (or the lack thereof), and

Predictability.

It appears that they are making progress on the second and third point, which affects my view of the first somewhat. I always want to give props where props are due, and when the delta of change is accelerating it’s important to take note.

As stated above, I do find the core product perfectly investable, and I believe this is no less the case today then it has ever been. As is often the case, however, many things hinge on the economics of management’s proposed growth strategy.

What is striking about the Grindr property is its apparent ubiquity in the gay community coupled with its ability to grow users with little, or even no, product innovation or reinvestment. This unusual characteristic begs the question: what is Grindr?

It’s probably safe to say that an outsider’s understanding of it is as a dating app. As I argued in my last piece, this is not quite the correct definition. A little scuttlebutt was helpful. In this regard, all I can say is that it’s a very different experience from the likes of Hinge, Tinder, and Bumble. Certainly, I was not accustomed to strangers propositioning me within minutes of creating a profile. There were no suave lines, no impressive profile pictures, and definitely no hours of monotonous swiping necessary to arrive at the possibility of an imminent encounter. I’m quite certain that the formality of a date was all but moot.

While the app is clunky and burdened with ad tech that is “so 2010”, there is absolutely no shortage of users, within walking proximity, who are interested in meeting up, if not a whole lot more. Without a doubt, the app is efficient in facilitating connections; users are presented either via a geographical map, or as a literal wall of suitors.

Within its own community, Grindr is more commonly referred to as a ‘hook-up app’, or as one user described it: ‘instant gratification on demand’. The company tries relentless to disassociate itself from this image, but even they acknowledge that users, who often have competing motivations for being on the app, are overwhelmingly interested in casual relationships:

On their own website, the company describes themselves as the following:

Grindr is the number 1 social network for the LGBTQ+ community.

Network, definitely. Social, partially.

Let’s stick with “network” for the moment. Grindr exhibits key characteristics of one of these discreet online networks that has remained largely unaggregated by the tech giants for understandable reasons. While Meta (specifically Facebook) has had a somewhat mixed history with online dating, their broad social mandate sometimes puts them at odds with the dynamics of seeking romantic relationships (casual or otherwise) online. Facebook may have hacked its way to ubiquity by brute forcing social connections, but this kind of connection would be disastrous in the context of selecting, and in turn being selected by, potential romantic partners. This gets even more complicated in light of non-traditional relationships, particularly those of the homosexual variety. “Coming out” is still an important and, crucially, intimate affair that usually proceeds the forming of any romantic relationships by years, if not decades. Indeed some people never declare their sexuality openly. In light of such considerations, the fact that Grindr stands alone from other social networks makes sense.

Unique social dynamics are one thing but the fact that Grindr stands alone from any real competitor is not exactly explained by it. Ultimately, it is just good at giving its users what they are there for, knowingly or not. The core feedback loop is incredibly strong. While management might claim that users come to Grindr for social interaction, travel advice, or even networking, users are (admittedly) there for an overarching reason. Unlike the ever changing and chaotic world of heterosexual relationships (predicated on things like status, wealth, and competition) which necessitates periodic platform shifts, a large part of the gay community (those who are interested in connecting online) have coalesced around a single app. Again, I ask the question: why?

To an observer, like myself, there seems to be no end of niche apps that are attempting to appeal to various LGBT+ groups. The reality is that while these populations may seem large in the aggregate, they are scant at the practical geographic level. While many users express frustrations with Grindr in online forums (especially when they are looking for less overtly sexual relationships) this doesn’t change the fact that there simply aren’t enough potential users in many geographies to support a discreet geographical network:

The negative feedback that Grindr receives publicly smacks strongly of the criticisms made of Facebook by its detractors not that long ago. Ultimately, all social networks are a reflection of their user-base. If one perceives Grindr to have failed in this regard, it has done so less by what it is then what it is not. If it effectively aggregates, and then connects users, than the company can hardly be blamed for what happens next.

So while the likes of Hinge and Bumble may cordon off a portion of the LGBT+ community (who are predominately looking for like minds without the instant gratification), Grindr keeps a hold of a large, and growing, audience. It has over 13M weekly active users (WAUs), and it shows no signs of slowing down.

Investor Day

In April, as part of our 15th anniversary, we publicly outlined our mission for the future, to be the global gayborhood in your pocket and, through its success, to make a world where the lives of our global community are free, equal and just. This mission resonates with all of us, I hope, because it's both descriptive and aspirational, descriptive in what Grindr is for a lot of users today and aspirational in where we will be taking Grindr in the coming years.

George Arison, Grinder CEO, 2024 Investor Day

The Investor Day was broadly broken up into two parts. Firstly, a long list of aspirational goals and targets largely piggy-backing off of Arison’s global gayborhood. Secondly, there was an excellent, although much terser, summary of what Grindr plans to do with their pricing, balance sheet, and excess capital. The latter was much more interesting than the former. You can find the presentation here.

In terms of product development, I think investors can expect an ambitious (potentially expensive) program:

As we scale Grindr to fulfill our unique role as the global gayborhood in our users' pocket, we will be building functionality for these various use cases that are already taking place in the app, but for which we do not yet have clear functionality.

As we do this, connection and casual dating, which have been Grindr's bread and butter since the very beginning, will remain front and center. But we also know that users want additional functionality to enhance the quality of their lives. This includes access to other broader sets of social relationships and community. They also want to have access to curated relevant information that will improve their life experiences.

These additional use cases are, apparently, networking, travel, health and wellness, and events - the so called gayborhood expansion.

Travel and events seem like a natural extrapolation of Grindr’s core geolocation functionality. To step back for just a moment, geolocation was, of course, a major causal factor in Grindr’s early traction, feeding into both the discreet network, and unique social dynamics narrative I elaborated on above. Arison shared his initial experience with Grindr during the presentation:

I'll tell a little bit of a personal story. I remember vividly the first time I learned about Grindr in 2009 when a friend of mine in D.C. pulled put his iPhone. We're at a bar, and suddenly, you could see all these people in the bar on the app. The power on that, at least on me, was really incredible.

I had been building a start-up on Blackberry at that time, and so I was not using an iPhone. But right after that experience, I went out and got an iPhone because I felt like I needed the app to use, and I was not the only one. In those early days, Grindr helped iPhone adoption in the community in a pretty significant way.

At the time, the primary use case was immediate casual connection to those around you. Over the years, this expanded largely organically with changes driven by the users. As a company, we now extending Grindr's use cases to follow our user behavior. We are doing this by focusing on their intent.

What is striking about the development roadmap is simply how far behind Grindr is in terms of core functionality that has been rolled out by the likes of Tinder, Hinge, and Bumble already. For example, front and centre during Arison’s presentation was Roam. This is the functional equivalent of Tinder’s Passport product. This simply allows a user to change geographic location without needing to physically be there.

The development of these products also opens up new revenue opportunities. As management noted, many of these products may be sold individually, either recurring or on a per use basis, or rolled up into packaged subscription offerings. While the outcomes of each is hard to determine ex-ante, it’s fair to say that these will be “build once, sell many times” in nature. Just like they have been elsewhere.

In any event, the company’s focus on Pricing & Packaging and Internationalisation is the real economic opportunity at hand:

So in general, we're early in our monetization journey. There's a lot of room to continue to improve and optimize. And the same is true for pricing and packaging. We are just building a product marketing capability internally now, which we expect to be able to deliver value here. And as we create these new features that add more value, we see a lot of opportunity to price and package those effectively over time. And we'll continue to use our product development process, which is kind of grounded in research and data and iterate that with AB testing to optimize the ecosystem overall.

Austin Balance, Grndr Chief Product Officer

And:

Just to add maybe one more financial component to that. What I would suggest is that when we're thinking about the free tier and the premium tier and what the value exchange could be, there might be 1 or 2 or maybe not, I'm not sure yet, which a la cartes that AJ described that might go into our extra or unlimited. And so I think that's how we're also thinking about packaging.

Vandana Mehta-Krantz, Grindr CFO

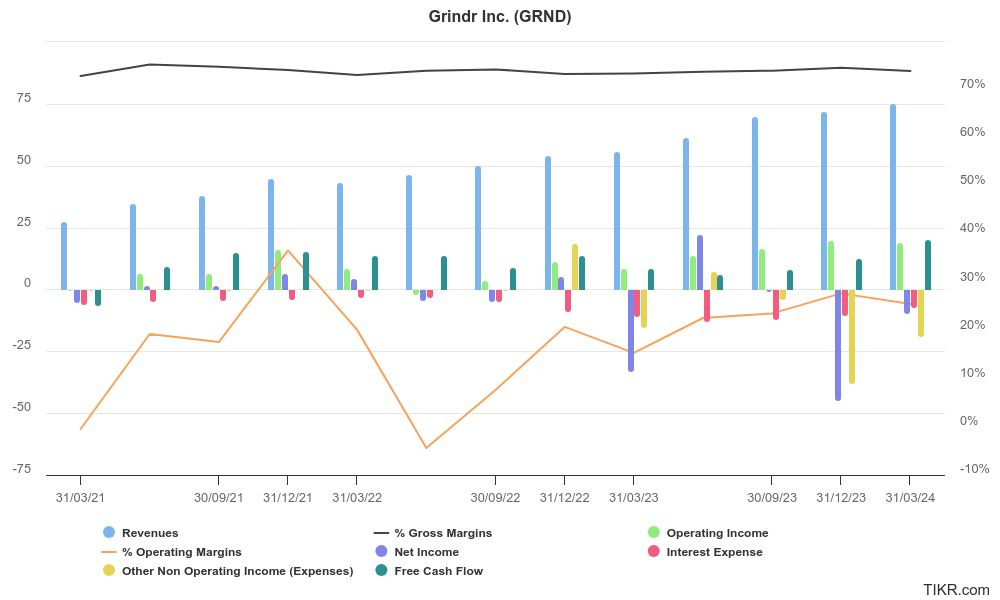

At a high level, Grindr has about 13.7M MAU’s, who, on average, spend a staggering 1 hour per day on the app. They have 1M users, on average, who pay to use the app in any given month, and those users pay an average of $21.25 (USD) per month. This contrasts (somewhat) against Bumble’s latest publicly available ARPU of $27.15. Average ARPU amongst the larger dating properties is somewhere in the mid $30s per month (USD).

Since going public, Grindr has grown MAUs at a high single digit rate, paying users at a high teens rate (roughly double MAU growth), and ARPU at a mid teens rate. This has been set against pretty stable base of employees (in fact Arison fired over a 3rd of the staff when they defied a return to office mandate in 2022), and a fixed asset base. You don’t need much capital to run an app.

The monetisation play is fairly straightforward:

The subscription options are:

Paying-walling new features and sequestering off parts of the former offering is a well trodden path by digital properties. The advent of Unlimited was a no-brainer and is just as close to pure price taking as, well, price taking.

To touch on the straightforward volume opportunity, Grindr management understands the importance of capturing discreet networks internationally. Where these populations are big enough (as mentioned above some of these communities are not very pronounced) they plan to invest. Arison was pretty clear about of having to offer a localised product offering to capture some of these nascent markets:

This is all perfectly aligned with the product localization efforts that AJ mentioned earlier. Our data shows that when our audience knows us, they're more likely to use us than a competitor. So the trick is to grow awareness to deliver results. We're currently starting to focus on building our brand in Spain and Spanish-speaking markets, where we have a big opportunity.

The importance of capturing as many large LGBT+ (especially gay) markets as possible is crucial to the long term growth opportunity - and Grindr is well placed to capture the lion’s share of that opportunity. As many online dating products go hand in hand with travel (of all varieties) it’s essential that Grindr secure as many discreet networks as possible to support and grow their own existing network.

We’re not talking about anything revolutionary, or even innovative for that matter, we’re talking about copying and pasting already successful products to drive monetisation, and more MAUs. On top of this, current subscriptions have proven pretty price insensitive. Most of the other major apps offer an ultra-premium subscription offering that can be well north of $50 per month, Unlimited is about $39.99 (with secular subscriber growth).

The company’s guidance in light of the above is impressive:

As a general rule I’m much less sanguine about the revenue opportunities in the additional use cases outlined by management as I am about Grindr’s plan to simply monetise their core dating use-case more effectively. We don’t have much to go on with regards to the former, but there are extraordinary opportunities in pricing, monetisation and organic volume growth from here.

Financials

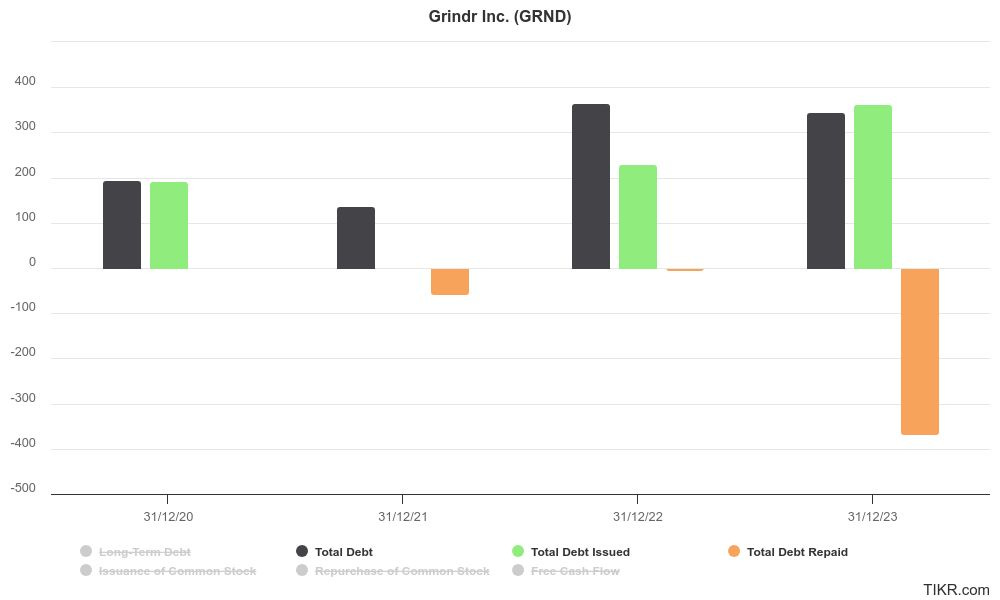

The first thing that comes to the eye looking at the company’s financials is its debt load. As of this writing, the company has net debt to EBITDA ratio of 3.27 times (this was 6 times in 2022). Naturally, when Grindr de-SPAC’d in late 2022 it raised a significant amount of debt to pay fees and issue one time dividends.

As Mehta-Krantz mentioned during the financial presentation, the company is primarily focussed on reducing its debt burden. They have done a good job of this since becoming a public company. Set against the back drop of strong financial performance (in cash), they shouldn’t have much problem affecting a beautiful deleveraging - that is a deleveraging driven by organic growth and cash generation. Importantly, management gave hints as to what they’ll do past this point:

Buybacks, pricing power, strong volume growth, and yet we are probably a little too early on in the piece to make definitive judgements about operational leverage.

While revenue growth has been extremely strong, operating performance has been much more volatile, and the company still reports negative net income (driven in part by interest and miscellaneous expenses). It’s important to note, too, that they exist within the ecosystems of Apple and Android, a precarious place to be for sure. A Sword of Damocles hangs over their heads. Likewise, as parts of world move to more populist and polarised politics it has been the case historically that societies become less tolerant of, well, tolerance. This could affect many of their markets - including their home market.

Valuation wise, it’s hard to determine value. While I’m confident top-line revenue will be strong, who can really say what happens below the line? You’re paying about 30x NTM EBIT/EV, which, quite honestly, could be very cheap or expensive:

As they mature, delever, and begin returning cash to shareholders, it will be much easier to get some conviction around what a reasonable price to pay should be.

Larry.