I recently read Andrew Walker’s piece ‘Is there a quality bubble?’:

Seeing how I am very exposed to this particular factor - although I don’t think, or measure risk in these terms - I thought the general idea is worthy of a reply, and a little introspection.

Andrew’s premise:

Another trend that I think has the most widespread implications has been the huge run up in stocks that are “GARP-y” (Growth At A Reasonable Price). In fact, many of these stocks have run up so much that I’m no longer sure if they qualify for the “at a reasonable price” part of GARP. Without the “reasonable price” piece, I’ve started to internally think of these companies and their run ups as a potential “quality bubble.”

A perfect example of this (potential) bubble is Costco. No one doubts Costco is a fantastic company, but my god does it trade richly. Charlie Munger famously called Costco a “perfect damn company” except for the fact its stock traded at 40x earnings…. and Costco’s stock has only continued to run since that quip. Today, the stock trades for ~50x earnings!

Again, no one is doubting Costco is a great company. It’s got a great moat and the model is hugely defensible….. but it’s not a huge growth company.

Given Andrew’s Costco example, I certainly agree. There are segments of the market that, while predictable and quality, are regularly priced at levels that the underlying companies simply cannot live up to. Something like Hershey’s comes to mind too. Even with the recent sell off, outperformance seems unlikely given the expected rate of return.

The usual proponents of the ‘a great company isn’t a great investment’ tag, however, are never categorically wrong, they are only ever wrong (sometimes in a big way) in each specific case. If you’ve been investing for a while you’ll no doubt be aware of the ‘Nifty Fifty Bubble’, and the famous historical analogues of Coca Cola and Microsoft in the early 2000s. Each are a paradigmatic example of expectations veering sharply away from reality. Any reference to price without context is intellectual laziness. This is how the Grahamian approach often goes wrong: exposure to so called cheapness, in a vacuum, isn’t enough to ensure acceptable results today.

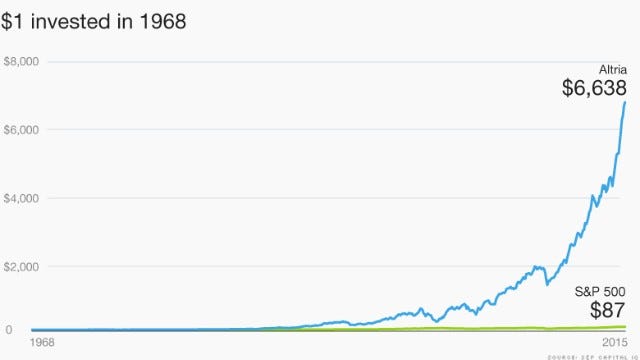

It is true that the Nifty Fifty Bubble popped. It is also true that if you purchased Phillip Morris at the top of this particular market extreme, and held it for 20 years you would have handily outperformed the general market. Context matters mightily.

I’ve mentioned this a few times in the past, but when interest rates were really low (i.e. when the ten year was trading <2%), I was always surprised by the multiple “safer” large cap companies traded at. I could understand buying a company like COST for 50x P/E (or a 2% earnings yield) when the ten year traded under 2% because you could look at COST at 50x and say “I’m getting near certain growth and inflation protection at a larger yield than treasuries (plus the tax advantages of long term compounding versus interest rates!); sure I think it’s rich but the opportunity cost makes sense.”

Again, no particular argument here. What appears to be a structurally higher rate environment has changed the minimum clearing price at which equities will represent value. That can only be the case where there is either more near term cash available to shareholders, or there is the very certain prospect of proportionally more cash later on.

Andrew also lays out three thought provoking questions, and hopefully I’m well placed to offer an answer to each:

I’ve been wondering what’s these prices / valuations. It’s easy to point at something like Costco and say “index flows,” but it’s hard to point to a smaller company like CMG or WING and say that some type of index flow is causing the valuation inflation. Is there something else going on?

I am reminded of an old Greenwald quote:

If you’re going to buy growth there’s a few things you need to understand. This is the drinking and driving activity of the value investment world. Understand that the value of growth is least reliably estimated, it’s highly sensitive to the assumptions, and… in the old days value investors wanted the growth for free.

I think there are a number of general observations that are important here. While I don’t want to be thrown in with the ‘this time it’s different crowd’ there are some things which are different this time. We live in a world with structurally more efficient businesses than 50 or 100 years ago. The number of employees needed to generate $1M in revenue in the Fortune 500 steadily marches downwards.

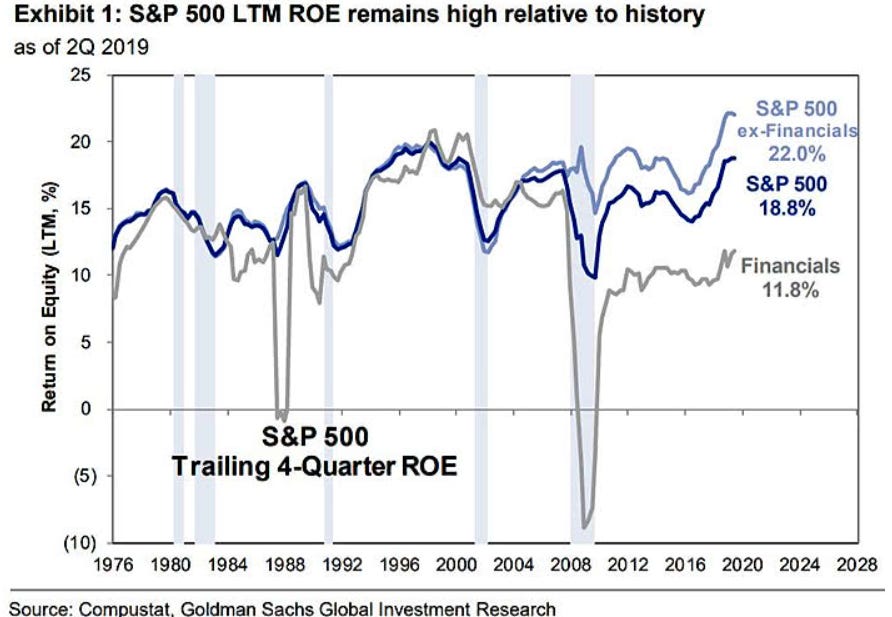

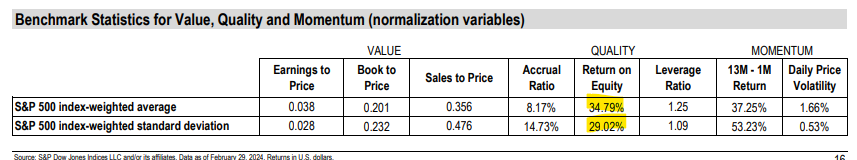

While the internet has been a big part of this, it is merely a symptom of humanity’s ability to innovate and deliver ever greater products and services over time. Despite our woes as a species, new technology continues to enable us to do more with less. The output of this is has been higher ROEs across the board when you strip out impact of financials:

We are living in a world of greater business returns, higher profit margins, and it’s all enabled by efficient scale and the ever greater ability for media and software to proliferate. Everything is being turned into a service.

In such a world equities are worth more. When you consider that the largest companies in the world are still growing at surprisingly high rates, and maintaining high returns at the same time, it makes sense. It has been a paradigm shift that has happened slowly, but perhaps as growth becomes more predictable (in certain parts of the market at least) that growth has become more valuable. In response to Greenwald’s point, perhaps today it actually pays to pay up for growth, especially when returns scale with it.

Markets are really competitive places; these stocks seem quite richly priced, but I have been wondering: what’s the other side of the argument? You only buy a stock because you think you can generate long term alpha; what’s the argument for generating alpha buying any of these stocks at the current prices?

I won’t defend the single stock examples that Andrew gave, but I can defend other richly prized names that I think are not in a bubble. For context, if you follow the newsletter you’ll know that I own more than a few names with near term earnings ratios in the 40-50x’s range. In such examples, they exhibit extreme pricing power made available by certain historical circumstances. In such cases it can make sense to own equities with rich current valuations but very interesting futures.

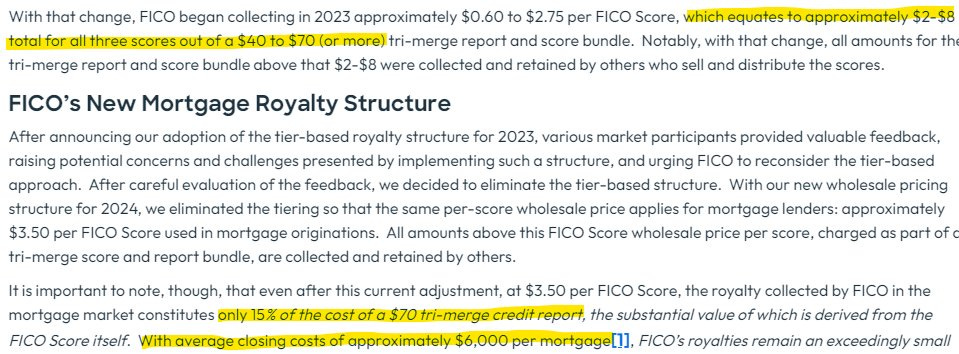

At the risk of sounding like a broken record, I’ll give the example of FICO. In a recent blog, CEO Will Lansing made the following admission:

If you have a small component, priced at less than 0.15% of the total cost of the larger value chain, and you have been raising the price of that small component well in excess of 100% a year, what is that worth?

A whole lot I would contend. This is compounded by the fact that many investments today are finding it difficult to offer returns above the rate of inflation. Real returns, well in excess of inflation, are prized assets in almost every environment.

I’ll even concede that insulation from inflation has become the market’s fascination du jour. Many mania’s start as good ideas, after all. However, context makes all the difference.

Again, the point of investing is to generate alpha. I don’t really see a way to generate alpha in these types of stocks from current prices, so I won’t be buying them…. but I do think one interesting thing to think about when looking at stocks is “could it catch a quality multiple expansion?” Let me give an example: BJ’s trades for <20x current EPS. It’s not as good a business as COST, but obviously it’s a similar model and it’s still a pretty high quality business. I think ~20x EPS seems fair-ish….. but I think you could look at that multiple and say “I’m paying a fair price plus grabbing a free upside option that it joins the quality club” and trades for 30-50x earnings at some point. Looking for that set up is a pretty interesting way to grab optionality in the current market (IMO).

I will concede that finding a high quality stock that has the potential to permanently re-rate is in some ways my entire strategy. It is, of course, much easier said than done. I think most of us see equity valuations as outputs of a variety of different factors. Most reliably, the microeconomic factors (those that are not extrinsic to the business) that affect valuations tend to be growth, the reliability of that growth, the returns generated by the business on the shareholder’s equity, and the margin structure. The dramatic exercising of pricing power is the surest way I know of to achieve enhanced scores on all fronts. To riff on my earlier point, those companies who have been able to make inflation work to their benefit, and who have been able to price well above it, have been rewarded handsomely in this market.

I continue hunting for them everyday.

So to answer the question ‘are we in a quality bubble?’ - I would say we might be, except in every particular case!

Larry.

P.S - for any of my American readers, I’ll be attending the Berkshire Hathaway meeting in May and I’ll be in New York City for the week after it. If you’d like to catch up for a coffee (sorry no boozing this year) be sure to drop me an email.

Nice write up. The market doesn't seem to worry about the higher 10 year I guess as they see multiple cuts this year. If no cuts happen as inflation is sticky at won't point will the market pivot? My guess is if there are not cuts in September but still a much lower probability than consensus.

Putting aside for a moment the content (which I heartily agree with), allow me to say this is just flout-out well-written (as in, the prose), with quite a few clever turns of phrase. (Not surprised that this is the case, given Sir Humphrey adorns the Stack!)