[Research] Farmer Mac

Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corp

Not held.

As always, if you enjoy the previews please take advantage of the free trial and free article.

Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corp (Farmer Mac) is a lesser-known government-sponsored entity (GSE) that operates in the agricultural sector. Unlike the GSEs that support the 30-year fixed-rate, fully prepayable mortgage regime, Farmer Mac has been both directed by Congress to and has organically moved into related lines of business over the years. Its long history of continued operation stands in stark contrast to the blow-up of Fannie and Freddie.

I. History

The U.S. government has been involved in financing its agricultural sector for well over a century. Woodrow Wilson passed the Federal Farm Loan Act of 1916, which created the Farm Credit System (FCS). FCS is a collection of borrower-owned lending cooperatives that operate under federal license. This original intent of Congress in essentially subsidizing loans to farmers was to provide more regular financing to a critical national industry that was subject to commodity volatility. This, and related agencies, continued to support farmers with low-interest loans into the Depression, and up until the farming crisis of the mid-1980s. FCS, and its related institutions, is largely seen as the first GSE.

Farmer Mac, by comparison, was established by the Agricultural Credit Act of 1987 as a secondary market for agricultural loans. It was formed by Congress in the wake of the financial crisis catalyzed by speculative agricultural lending in the mid-1980s.

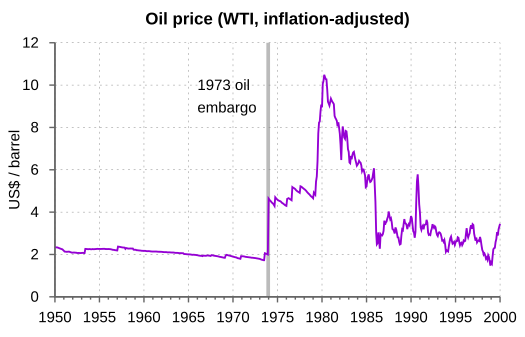

Beginning in 1973, many long-standing trends in North American farming began to reverse. Since the dark days of the Great Depression, farming was becoming ever more mechanized, greatly reducing the need for agricultural labor and subsequently its cost. This was at first a boon to landowners, who had also experienced several decades of modest input cost inflation coming out of the Second World War. On the other hand, the increasing productivity of farmland led to large crop surpluses in these years, often negating operational efficiencies experienced elsewhere. During October 1973, OPEC began an oil embargo of those countries that had supported (or who were seen to support) Israel in the Yom Kippur War. This kicked off a large inflationary shock in the Western World which would need about a decade to be brought under control.

With oil prices effectively doubling overnight, farmers in the U.S. began to experience the largest input cost inflation that they had experienced in decades - as oil is a major component in both fueling mechanized farming equipment as well as being a critical input to fertilizer. At first, this had the effect of materially decreasing the profitability of various crop yields. Uncle Sam then intervened rather clumsily. While the U.S. was still experiencing considerable crop surpluses in 1973, the USSR had experienced several years of crop failures, especially in wheat. In mid-1973, the U.S. government signed a wheat export deal with their counterparts in Moscow. U.S. negotiators were completely unaware of the dire state of the crop failures in Eurasia, and indeed in many other places in the world. In one of those strange twists of history, the successful launch of Landsat 1, the first earth-orbiting satellite capable of taking high-fidelity imagery, occurred one week after the negotiations concluded. Had these events taken place beforehand, it’s unlikely that the deal would have been made at all, and perhaps the U.S. could have sidestepped one of the worst inflationary shocks of the last century. Alas.

Not realizing the strength of their bargaining position, and indeed keen to ameliorate the structural surpluses they had been experiencing for some years, U.S. negotiators at first offered to sell produce to the USSR on credit. When that credit limit was immediately exceeded, these representatives effectively offered to sell wheat to the USSR for heavily subsidized prices. Dubbed by posterity as “The Great Grain Robbery”, Uncle Sam’s missteps kicked off structural crop shortages in the U.S. for the first time in decades. A basket of popular crops nearly tripled over the next two years.

While long-term U.S. rates experienced a short-term peak in 1974, rates generally ameliorated for the rest of the decade. This circumstance, coupled with the increasing profitability of crop yields, kicked off a classic debt-fuelled speculative frenzy in agricultural land. Successful farmers, and speculators, borrowed heavily to acquire machinery, equipment, and land in the run-up to 1980. FCS (which has historically been responsible for about half of all agricultural lending) saw a doubling of lending to farmers between 1973 and 1979.1 The party was not to last.

In December 1979, the USSR invaded Afghanistan. The U.S. responded by enacting a grain embargo, effectively causing U.S. agricultural exports to decline by 20%. The severe inflation of the late 1970s was, however, about to experience a severe remediation. Paul Volcker was appointed to chair the Federal Reserve Board in August 1979. Over a weekend in July 1981, he would raise the Federal Funds rate to 20%. The combination of nearly unprecedented changes in the cost of capital, as well as the mounting surplus of crops in North America began to kick off a wave of insolvencies. A typical deflationary financial bust sees declines in the price of economic outputs, and asset prices, while outstanding nominal debt balances remain the same. As liabilities remain fixed, and indeed compound with interest, deflationary commodity prices have the effect of making producers more indebted as they scramble to sell produce to satisfy those debts. This cycle began to garner public attention in 1984. Between 1985 and 1988, the crisis experienced its most torrid phase. In 1985, 62 agricultural banks failed. By 1990, 300,000 farmers had defaulted on their loans.2 The price of farmland in many Midwestern states had declined by over 60% by the end of the 1980s. Congress, recognizing its responsibility to manage the crisis, stepped in.

Over the course of these events, Congress passed the Food Security Act of 1985, introduced Chapter 12 bankruptcy in 1986, and the Agricultural Credit Act of 1987. Farm consolidation, and the drought of the late 1980s and early 1990s also went a ways to make U.S. farming sustainable over the following years.

As part of the Agricultural Credit Act of 1987, FCS was awarded a $4B (real money at the time) bailout. Its failures in foreseeing, and indeed abetting, the crisis were noted by lawmakers. Over the course of the nearly 300,000 farm failures, it was also encumbered in its ability to offer timely liquidity to parts of the market, exacerbating the acute pressures being brought to bear on overleveraged borrowers. While the FCS system had been engineered to offer farmers heavily subsidized loans, its structure did not necessarily enable it to be any more efficient than what traditional primary market lenders were historically. Consequently, lawmakers looked to the home lending GSEs for inspiration in creating a secondary market for agricultural loans.

And so Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corporation was created. For its first 15 years or so of operations, Farmer Mac primarily securitized loans, purchased loans, and also guaranteed agricultural loans. When Fannie, Freddie, and to a more modest extent, Ginnie Mae, securitize mortgages, they do so by ‘pooling’ groups of mortgages together. The effect of socializing the risk of default across borrowers, and by also insuring the bonds, they offer a de-risked product to investors. Value is created because Treasury de facto guarantees the bonds. Uncle Sam’s low cost of capital can be used by proxy to the benefit of an individual mortgagor. In the case of Farmer Mac, borrowers are not as numerous, nor are they as uniform. Over the course of the last four decades, it has come to light that the majority of state-sponsored agricultural lending has been concentrated in the hands of a few thousand borrowers. This creates a lumpier, and somewhat less predictable business initially, but the core value proposition remains: using Uncle Sam’s license, lending institutions can free up their balance sheets by offloading assets to the new secondary market made possible by the existence of Farmer Mac. FCS would continue to operate, and arguably operate even more effectively now that a secondary market existed.

The seeds of Farmer Mac’s first crisis were sown during its creation. Its initial mission was threefold: to increase liquidity to agricultural lending, to improve the availability of long-term lending, and to stabilize interest rates in these areas. There’s nothing wrong with any of that. That mission was broadly directed at farmers, farming communities, and residential real estate connected to farms. By the end of the 1990s, it was becoming apparent that the original regulatory parameters set by lawmakers were not sufficient to keep Farmer Mac’s practices totally mission-focused. No, by this time the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) had been asked by Congress to investigate certain “non-mission investments” made by Farmer Mac. This devolved into a more serious inquiry into management practices, corporate governance and accountability, and succession planning.

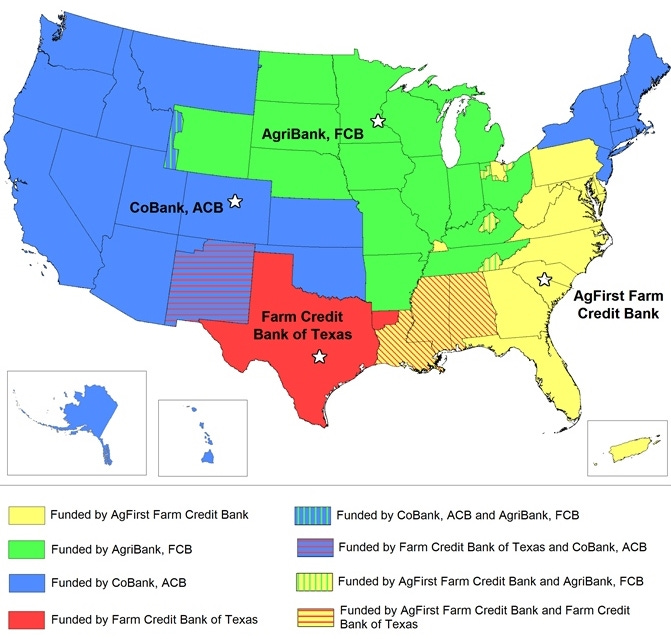

In short, Farmer Mac executives were using more than a quarter of their excess balance sheet liquidity to essentially speculate in equities, and preferred issues, often sold to them by the very banks who were their counterparties in their secondary market business. This would mirror, and indeed precede, Fannie and Freddie’s descent into mortgage speculation a few years later. In Farmer Mac’s case, a 2005 finding by GAO resulted in this practice becoming illegal. This inquiry also focused on Farmer Mac’s loan loss estimation model. When Farmer Mac began operations, it naturally had none of its own historical loan data to estimate losses under. In lieu of this, it decided to exclusively use historical loan loss data provided by the Farm Credit Bank of Texas. At the start of operations this was probably okay, but the issue with only using data supplied by a regional Farm Credit bank was that it wasn’t necessarily representative of the country-wide business being done by Farmer Mac nationwide. One of my friends, who comes from a long line of St. George cotton farmers, once told me: ‘there’s always a f*ck-up in some kind of farming somewhere’. While that’s especially true in Australia where the environment experiences serious weather volatility, it is also true in the more moderate environs of North America. At one time or another, some variety of agricultural endeavour is undergoing severe hardship somewhere. Texas, for example, is not Nebraska. The decentralized banking system of FCS plays its role, but it is not a centralized endeavour intermediating risk like Farmer Mac is.

As posterity would prove out with Fannie and Freddie, incorrect loss estimations, security speculation, and poorly aligned management incentives are a recipe for disaster - so much so that it nearly resulted in the end of modern capitalism. By the end of 2005, senior management had been completely turfed out of Farmer Mac, a new lending model based on its own historical data was implemented, and the purchase of assets for its balance sheet became regulated and scrutinized. All hunky-dory. Sort of.