[Research] PEXA Group Limited

A monopoly on 'hoom' transactions down under

Not held.

All dollar amounts are in Pacific Pesos (AUD) unless otherwise mentioned.

As always, if you enjoy the previews please take advantage of the free article and trial.

I have written a little about e-conveyancing in the context of Canada’s Dye and Durham. Conveyancing is, of course, the transfer of real estate from one person to another, during a property sale. For reasons I won’t go into here, property ownership, and naturally its transfer, is really one of two major bedrocks (the other being offences against the state and other people) on which Anglo-Saxon legal systems are built. In the medieval and early modern periods of Western Civilization, land ownership was the most enduring claim on a country’s productive economic output. Land ownership scales, as do its rents. As economic surpluses have accrued elsewhere in the modern era, land ownership has continued to be a pretty good (maybe even excellent depending on your location) store of wealth, but for very different reasons. Those new economic surpluses often find their way into desirable residential locations (proximity to good schools, amenities, and high-paying work opportunities), and governments have sought to encourage this as a way to curry favour with voters and raise revenues simultaneously. To some success, too, I might add.

In the modern Anglosphere, the most significant economic transaction an individual is likely to make in their lifetime is the purchase and the disposal of real estate. These transactions are highly regulated by the state for governance and revenue reasons. In Australia’s case, real estate transactions (not necessarily land taxes, although these do exist) have been a way in which state (or let’s say provincial) governments have gone about funding themselves. The most prominent example of this is Stamp Duty. This tax is named as such because it was historically paid when a government official literally stamped the documents recognizing a change of ownership. This is typically calculated as a percentage of the home value (somewhere in the realms of 3%), but there are an array of stratifications and exemptions depending on a variety of factors (typically whether or not a first-home buyer is involved). The policy impulse of state governments in this regard is to encourage transactions and to have higher home prices. At the limit, the government has a much easier time stimulating home values. Put another way, one can push pricing much further than one can sustainably increase the velocity at which homes transact. On a median income to median property value basis, Australian capital cities sit just shy of Hong Kong in terms of affordability. This has been taken to levels which I would have thought to be outside the realm of practical reality—but that is neither here nor there.

As with many government processes, it was only until relatively recently that the business of actually transacting and transferring property was an analogue affair. What would often complicate and prolong this process was that for a property to be transacted, multiple steps would need to be taken between a number of parties—often in person. Before the days of electronic communications and the internet, this made sense. Nowadays, not so much. The process was costly, and its inherent inefficiency was costly for all involved (including the government). Waves of e-conveyancing software were developed in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s, but Australia had a far less grassroots origin in the creation of its digital exchange and conveyancing infrastructure.

In 2008, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) introduced e-conveyancing as part of the Seamless National Economy deregulation priorities. This was followed up by the creation of National E-Conveyancing Development Ltd (NECDL) in 2010 to develop a national e-conveyancing system. The NECDL was initially formed by the state governments of Victoria, New South Wales, and Queensland (the states occupying the east coast of Australia), and the “big four” national banks. Western Australia joined not long after the formation. In 2011, the Australian Registrars’ National Electronic Conveyancing Council (ARNECC) was formed under the Intergovernmental Agreement for an Electronic Conveyancing National Law to coordinate a national legal and regulatory framework for e-conveyancing operators. ARNECC subsequently approved NECDL (later reorganized as Property Exchange Australia Ltd, or PEXA), and would later approve an ASX (national stock exchange) and InfoTrack joint venture known as Sympli.

Australia is a federation of six states (Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia) and two internal “territories” (the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory). There are a number of overseas territories, but in the past couple of decades, more of these have been joining various states as a way to escape federal exactions. States technically represent the “Crown” and enjoy a form of sovereignty under a typical Westminster system of government with their own viceregal representative. They split responsibilities with the “Commonwealth,” or the federal government. Territories, however, have a subordinate position with respect to the Commonwealth, and the latter can unilaterally intervene in their affairs. For example, under the Howard Government, the Commonwealth began a virtual military occupation of the Northern Territory. States, however, have the responsibility and powers necessary for recognizing and taxing land transactions. So you can get a feel for the potential of a powerful network effect here. Certainly, where a federal government agency acts as the gatekeeper for even getting started in the space, this is doubly true. Getting six different states to agree on anything is difficult, but getting so many different conveyancing regimes to operate through a single exchange can lead to efficiencies.

I’ll make a broader observation here about network effects. It’s been often observed that for a networked business to get traction initially, it must be as useful to its first user as it is to its n+1000th user. The role of the government, and this can be extended to mutually owned operations generally, can often be to coercively bridge the gap between organic initial adoption and the network benefits and efficiencies enjoyed when the network is in full swing. This is very much what happened in the very early days—the fact that the big four banks, who are the principal mortgage issuers nationally, also came along for the ride was likewise very auspicious.

Across the groups that are party to a property transaction (state government land and revenue offices, lawyers, conveyancers, financial institutions, buyers, sellers, and the latter’s two agents) all apparently enjoy time and cost savings by the implementation of a central e-conveyancing system. As the federal government’s directives stated from the onset, this was the driving force behind the development of PEXA.

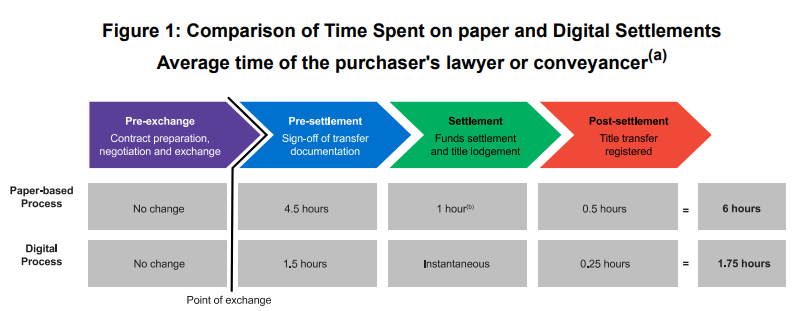

The key efficiencies gained in time are really represented in the automation and digitization of document exchange and sign-off, settlement, and title transfer. As you can see above, the time saving here is more than four hours. You can imagine the prevailing hourly professional rate as the start of the cost savings. Having said that, the implementation of e-conveyancing systems also includes trade-offs for additional time commitments in return for greater certainty. The prime example of this is in the pre-settlement data verification processes, which, in addition to the use of data sharing, drastically reduces the probability of a transaction failing or being fraudulent. However, because the time savings at the aggregate level of the pre-settlement stage is so large, the trade-off is still a substantial positive. The efficiencies are not only experienced by the transacting parties—financial institutions also save money on the vastly reduced use of checks (cheques), couriers, and administrative staff necessary to coordinate the old analogue steps. Follow up investigations into e-conveyancing by the federal government indicated that the all-in cost savings of moving all property transactions in Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria would be almost $100 million AUD in 2018.1

From a positioning perspective, a “network operator” (e-conveyancing exchange), or what has since become known as an “electronic lodgement network operator” (ELNO), sits between parties along both the vertical and horizontal axis at various stages of a transaction. At the pre-exchange and pre-settlement point, the buyer and seller and their agents (conveyancing professionals, lawyers, and other agents) are the main participants. At the settlement and post-settlement stage, integrations with financial institutions and various payments infrastructure and government agencies occur. This should be somewhat obvious, because at settlement, funds are transferred, and after this point, the property title is transferred. In Australia, the transfer of these funds takes place via a payment mechanism operated by the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) (both a central bank and a payments regulator)—the Reserve Bank Information and Transfer System (RITS), Australia’s interbank settlement system. RITS operates on a ‘reservation of funds’ settlement model. The purpose of this is to ensure a timely and actual exchange of title and funds simultaneously. Most Australian non-cash, larger dollar transactions occur through RITS, which is enabled through the debiting and crediting of the appropriate dollar amounts in the respective financial institution’s account with the RBA. A network operator connects to RITS through a ‘batch administrator’ who technically arranges the cash leg of the financial settlement. Network operators make the near-instantaneous settlement of titles and monies a possibility through an integration with the respective land title offices (state-based):